Take action on behalf of grizzly bears and their habitat

Yellowstone Bears are Unique

David Mattson

Imagine…

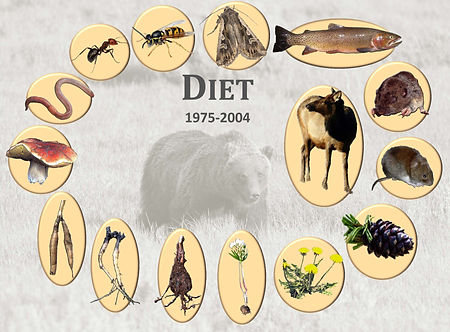

Imagine a grizzly bear on a cloudy day in May turning over chunks of sod in a wet swale to reveal clots of wriggling earthworms…which it then slurps up. Or, in the next valley over, a bear furiously hopping sideways as it excavates a tunnel in pursuit of an escaping pocket gopher, but then contenting itself with a cache of exposed roots that the gopher had made as winder provender. Or, earlier in the year yet, during April, a grizzly bear flopped on its belly in the middle of barren white sinter casually raking potassium- and sulfur-rich dirt into its mouth to consume as a spring restorative. Or a hulking male grizzly settling down to the challenging task of tearing the thick hide off of a winter-killed bison, with the prospect of days of feasting ahead.

Or a female with two cubs emerging from the shadows of a lodgepole pine forest one day in late September and strolling down into the dried-up bottom of a pond that had been inundated earlier that spring…and then systematically rototilling the mud to turn up the starch-rich rhizomes of a plant called pondweed. Or another bear deep in the adjoining pine forest scraping the duff to get at a bolete mushroom, and then digging deeper yet to excavate the illusive underground portions of a false truffle.

Nowhere else on Earth other than Yellowstone will you find bears of any species in any number engaged in these behaviors—focused on eating these foods. Or, if there are other bears doing these sorts of things elsewhere, it is extremely rare and very poorly documented; perhaps one other known instance of brown bears eating pondweed rhizomes, near Lake Baikal in Siberia. Or a few other instances of brown bears eating earthworms from under moldy hay in central Russia. But little more than that.

And then Imagine…

On top of this, Yellowstone is a bastion of behaviors directed at foods that may occur with modest frequency in other regions, but nowhere to the extent found in and around Yellowstone Park.

Think of a bear during mid-fall homing in on the chatter of a red squirrel to locate and then plunder the squirrel’s cache of whitebark pine seeds. Or of bears flocking to the great talus slopes beneath the tundra plateaus of the Absaroka Mountains to lick up army cutworm moths from under overturned rocks. Or of grizzlies patiently angling for spawning cutthroat trout up and down the smallish tributary streams of Yellowstone Lake.

Or of other grizzlies systematically working the windswept slopes of high ridges to excavate prime biscuitroots—at ever higher elevations as the season progresses. Or of yet other grizzlies meandering through verdant meadows skillfully excavating the starchy roots of yampa. And then consuming the succulent stalk of an elk thistle after carefully removing the protective spines with their claws.

My Point, in Case You Missed It

I hope that I’ve made my point without boring you. And, in case it’s not obvious, here is my point: the grizzlies that live in the Yellowstone ecosystem are incredibly special and unique. We have here habitats and foods and behaviors that are unlike any that occur anywhere else; if not altogether unique, then unique in the extent to which they do occur.

And then there is another important point. Some of the behaviors and foods that can be found now only in Yellowstone were once widespread. Which is to say that scavenging of bison carrion by grizzlies living on the Great Plains was once quite common (follow this link), as was consumption of yampa, biscuitroot, and pocket gophers in the mountains of Utah, Colorado, and Oregon (and this link). But no longer, thanks to widespread extirpations of grizzly bears perpetrated by European settlers. And, in this regard, Yellowstone is a museum of relics, a sacred place holding (what I would hope are) the cherished remnants of bear behaviors and even foods that were once widespread.

Having made these points, I realize that not all of you give a damn. Some of you may consider the rare and even irreplaceable behaviors and foods of Yellowstone’s grizzly bears to be entirely expendable and otherwise of little consequence. Which I would argue is, in itself, a profound commentary about all sorts of things. Which takes me to my next point.

The Rhetoric of Denial

Reflect for a minute. I invite you to try and remember any private or public instance where a government wildlife manager favorably commented on the collectively special, important, rare, or unique behaviors, foods, and habitats of Yellowstone’s grizzlies. Or even a government scientist for that matter.

Maybe you can come up with an instance, but I can’t.

The closest I come is a flurry of government press releases during the last two years flogging a 2013 white paper issued by the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team and a 2014 article by a government manager and scientist named Kerry Gunther. Ironically enough, the gist of this media push was to highlight the number of different foods eaten by Yellowstone’s grizzly bears as a basis for, in turn, utterly dismissing on-going and likely future losses of foods and behaviors. In other words, the various federal and state agency spokespeople quoted in this government-promulgated media were basically telling us that the rare, special, distinct, unique, irreplaceable behaviors of Yellowstone’s grizzly bears didn’t, in fact, matter. At least to them. (Parenthetically, I could go on at length about problems with this and other government science, but will refrain in service of my main thesis).

In fact, in this and many other instances, the tone adopted by government managers and scientists when describing losses of irreplaceable biodiversity has been almost gleeful.

So, we have little or no acknowledgement of behavioral and dietary biodiversity on the part of government bureaucrats and scientists or, when the uniqueness of foods and behaviors does come up, the focus is on utter, even perverse, dismissal.

And the Losses are Non-trivial

Is there reason to be concerned about losses? Absolutely.

We lost the majority of mature cone-producing whitebark pine in a single decade to a lethal epidemic of bark beetles driven by climate warming. Although there is some debate over whether whitebark pine will come back, I am skeptical. No matter what some apologists might say, our climate is only going to get warmer, with continued attrition of the high-elevation haunts of this pine species. And even under the best of circumstances, cone-producing trees are not going to be back any time soon.

We lost virtually all of the cutthroat trout that spawn in tributaries of Yellowstone Lake to a wicked one-two punch of predation from Lake trout (a recently introduced non-native) and worsening stream conditions that are ultimately attributable to climate change. Again, there is some debate about prospects for restoring cutthroat trout but, again, I am skeptical. There is essentially no prospect of ever eradicating Lake trout, and hydrologic conditions will only worsen, not improve, with continued changes in precipitation and snowpack.

We continue to lose bison to regressive and wrong-headed management strategies that have been implemented to address the presumed threat of a bovine disease called brucellosis. Thousands of bison in one of our few remaining free-ranging herds have been killed as part of a program to placate right-wing ranchers who use the inflated threat of brucellosis to cattle as a means of perpetuating an ideology of land use. Who knows where this all leads, but the slaughter of bison at the boundary of Yellowstone Park certainly precludes any availability of bison to the many grizzlies living on non-park lands.

We will lose most (say, 90%) of alpine habitats that currently sustain army cutworm moths as these environments surely succumb to climate warming during the next century. We don’t know if or how cutworm moths might adapt to climate change, but we do know that they currently subsist during the summer almost wholly on the nectar of flowers growing in alpine tundra.

As for all of the other foods and behaviors unique to Yellowstone’s grizzly bears? The future is at best uncertain. My experience with modeling the prospective effects of climate change on the distributions of plant and animal species has led me to a couple of firm conclusions. Major, virtually incomprehensible, changes will occur. Much of what we have now in Yellowstone will disappear, with little prospect that most species will simply migrate upslope. And much of what replaces these losses will be weeds.

And what about the bear foods that government managers and scientists so glibly promote as future replacements? Most of the berry-producing shrubs will likely diminish, if not go away altogether (think serviceberry, chokecherry, and buffaloberry). Elk will be hammered by worsening forage conditions and by the spread of Chronic Wasting Disease. And out-of-range foods such as Gambel’s oak (think acorns), will not likely reach Yellowstone or, if they do, the process will take centuries.

A Closing and Somewhat Disturbing Reflection

I close by going back to what my friend Susan Clark has called “the rhetoric of denial.” More specifically, the rhetoric voiced by our public servants. A rhetoric that profoundly disturbs me. A rhetoric that can rightly be considered propaganda (follow this link).

Not only do the government employees managing our grizzly bears consider the losses of biodiversity that we have seen (or can foresee) to be unproblematic in the end, but, even more disturbing, that irreplaceable bear foods and behaviors are of little consequence. Of so little consequence that these issues are irrelevant to Yellowstone’s cabal of federal and state grizzly bear managers. The rhetoric is all about denying problems, denying inconvenient values, and delegitimizing or dismissing any who would argue otherwise.

Which leads me to the perennial question of Why? A complete answer would require plumbing the depths of our institutions of wildlife management, the worldviews of those who populate this institution, and the interests and strategies of the political masters they serve. But something brief is warranted here.

If I had to reduce my answer to two intertwined essentials, the first (not surprisingly) would pertain to power. Most obviously, consideration of threats to the biodiversity entailed by diet and behaviors would only complicate the current rush to remove Endangered Species Act (ESA) from Yellowstone’s grizzly bears, which is a consummation devoutly wished by the states of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. Less obviously, those in the government who are pushing back hardest on consideration of behavioral “intangibles” are probably doing so partly out of resentment—resentment of those bringing the argument and the long-term threat these folks have posed to their petty power.

But, perhaps more importantly, I suspect denial is rooted in worldview. There is little doubt in my mind that current approaches to wildlife management are founded on the impulse to instrumentalize and objectify; to reduce all animals to objects which, in the process, more readily satisfy the raw impulses of mostly-male hunters intent on making meaning through killing stuff. To reduce animals to mere cyphers on the balance sheet of population counts, translated into heads on the wall.

I suspect that the net result is a visceral resistance to seeing and valuing animals as individuals--as emotional sentient beings enmeshed in rich and complex relations with the world around them. What a pity for the wildlife managers who live such an impoverished life. And what a tragedy for the animals prey to the impulses of these managers.